2025.03.13

Distinguished Professor Yu-Ju Chou (周育如) of NTHU's Department of Early Childhood Education (first from the left) and Associate Professor Tsung-Han Kuo (郭崇涵) of the Department of Life Sciences (second from the left) guiding children to cooperate in games.

When the aggressive behavior of mice is suppressed, they begin to exhibit prosocial behaviors such as allogrooming. A cross-species study conducted at National Tsing Hua University (NTHU) in Taiwan has found a similar pattern in young children, suggesting that after learning self-control, they tend to engage in more positive interactions and altruistic behaviors, which can have long-term benefits for their future interpersonal relationships and mental health.

The merger of NTHU and National Hsinchu University of Education facilitated an increase in cross-disciplinary research in fields such as education, the arts, and biomedicine, including this remarkable cross-species study on young children and mice conducted by a team led by Distinguished Professor Yu-Ju Chou (周育如) of the Department of Early Childhood Education and Associate Professor Tsung-Han Kuo (郭崇涵) of the Department of Life Sciences. Their research has been published in a recent issue of the international journal Behavioral and Brain Functions.

Kuo said that animals exhibit a wide range of social behaviors, including aggression and dominance competition, as well as prosocial interactions that foster social harmony. Using a resident-intruder assay, the study found that male resident mice housed alone for a week displayed aggression towards other mice introduced into their cage. However, when the brain regions responsible for aggression were lesioned, their aggressive behavior ceased and was replaced by allogrooming.

“This seems to show that mice are inherently kind!” said Kuo, adding that while aggressive behavior serves an evolutionary role in survival, the instinct of kindness and altruism has not disappeared, it is simply hidden.

Chou, who specializes in early childhood education, conducted a corresponding one-year study on the self-control abilities of more than 100 children aged 4 to 6. The results showed that children with better self-control were less impulsive and aggressive while being more inclined to share, care, help, and cooperate—findings that align with the results of the mouse experiment.

Chou explained that before learning self-control, young children tend to act on impulse—for example, grabbing a toy as soon as they see it or hitting back when struck by a playmate. As self-control improves, children learn to raise their hands before speaking, take turns with toys, and resolve conflicts without overreacting.

“Self-control can be learned and is more important than book knowledge,” said Chou, emphasizing that beyond teaching children not to hit or bully others, it is equally important to encourage kindness and nurture their emotional quotient (EQ). Young children who develop self-control and positive social skills are likelier to grow into mentally healthy adults.

Chou is currently conducting a new experiment aimed at improving children's self-control. By using music, dance, and rhythm, she has demonstrated that it is possible to improve children's self-control significantly. Moreover, the participants showed improved concentration, became less prone to temper tantrums, and were more likely to wait patiently in line. They also exhibited a greater willingness to help one another and cooperate during play.

Chou stated that humans and animals are born with altruistic motivations, and strengthening self-control not only curbs aggressive impulses but also fosters increased altruistic behavior and more positive interactions. In addition to deepening our understanding of animal social behavior, this cross-species study provides new insights for preschool education.

Chou (third from the left) and Kuo (third from the right) guiding children to cooperate in games.

Chou (third from the left) and Kuo (third from the right) guiding children to cooperate in games.

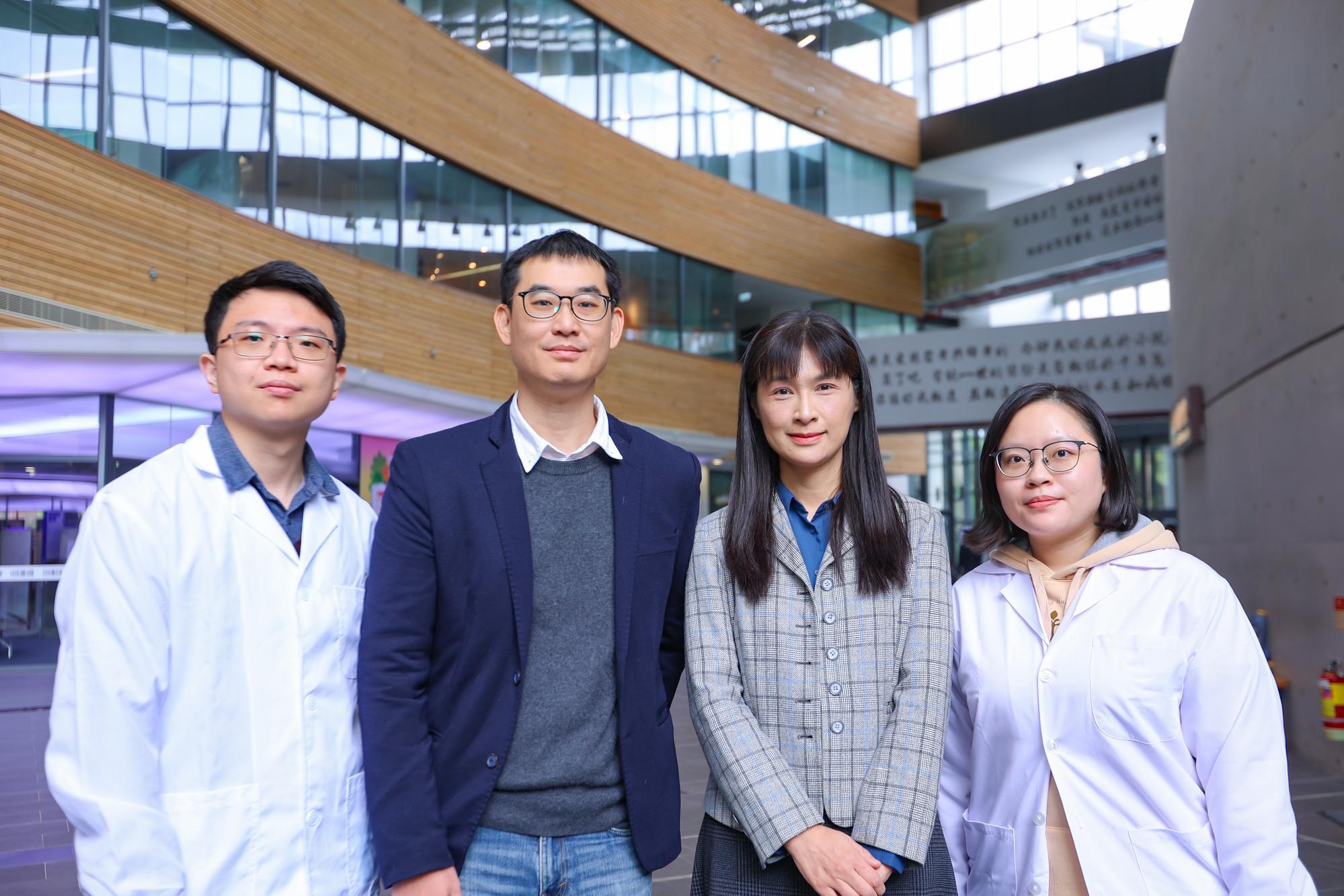

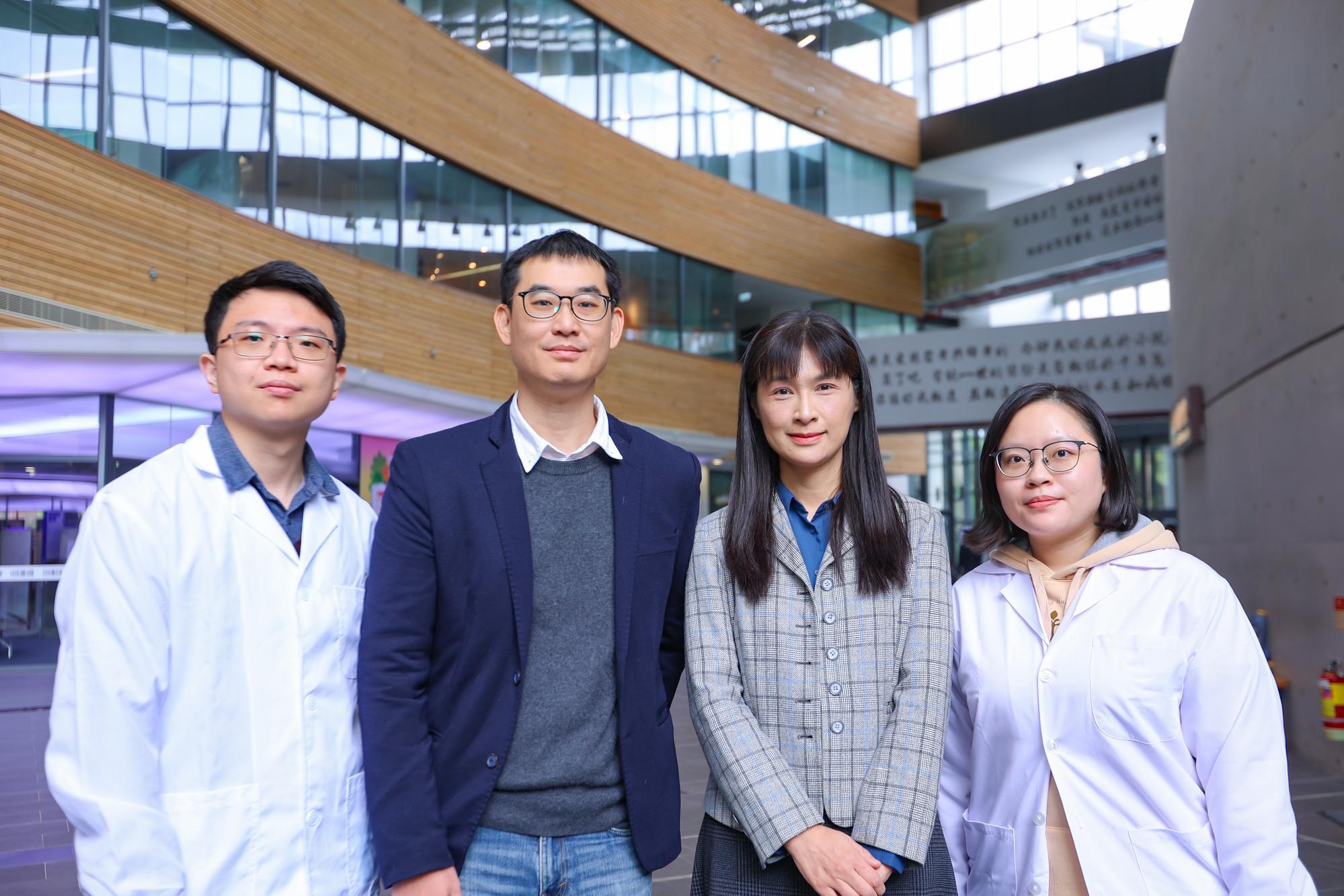

Chou (left) and Kuo conducted an innovative cross-species study on social interaction.

Chou (second from the left) and Kuo (second from the right) guiding children to cooperate in games.

Members of the research team (left to right): Institute of Early Childhood Education master's student Jin-Ping Wu (吳錦平), Institute of Systems Neuroscience doctoral student Chih-Lin Lee (李知霖), Kuo, Chou, Institute of Early Childhood Education master's student Chi-Yu Chang (張積育), Hui-Ping Lin (林惠萍), and Xin-Ni Chen (陳昕妮).

Members of the research team (left to right): Lee, Kuo, Chou, and Chang.

The research team used specialized equipment to measure the participants' brain waves.

Chou showed that it is possible to improve children's self-control to a remarkable degree through music, dance, and rhythm.

When the brain regions responsible for aggressive behavior were lesioned, the aggression of the black mouse ceased and was replaced by allogrooming.

Mice getting to know one another in Kuo's experiment.